Well, allow me to amend that. It must really suck to be Amy Chua until the royalty check arrives.

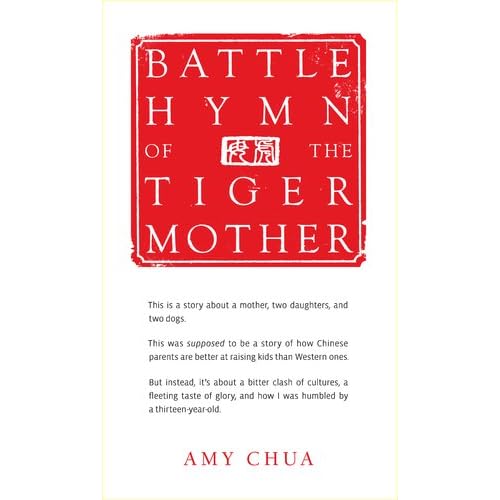

Ms. Chua is the author, if you haven't heard by now from lots of other livid blog posts, of Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, a memoir about how she applied the strict, Asian-style parenting she herself grew up with to raising her two very American daughters. Though her descriptions of her style of parenting sound pretty heavy handed (and a little shrill), by the end of the book she apparently relents in the face of her younger daughter's (inevitable) rebellion and pulls back a bit.

Full disclosure: I have not read the book - only a lot about it. For most (who probably have not read it, either), it was likely this essay from the Wall Street Journal that introduced them to Chua and her parenting philosophy.

From this essay and further interviews, like this one in the New York Times, Ms. Chua sounds like plenty of other parents I have known both as a kid and as a parent myself. I'll also note that from the WSJ piece, while her tactics seem on the harsh side, not all of her philosophies are disagreeable.

As a result of the WSJ and her book, Chua has received death threats - and lots of publicity, praise - and lots of publicity, and scorn - and even more publicity.

She shouldn't be surprised, because whenever you put yourself out there with something as private and personal as parenting, you can be guaranteed that lots of folks are going to have something to say in response. The part that sucks is that what many people are saying is that Chua is a really bad mom.

I personally have no experience with Asian style parenting other than what I have read about or dealt with by seeing its results in adults. Yes, it's a common stereotype that Indian, Chinese, Japanese and Korean students will always - always - beat the pants off Western kids in anything academic. And Chua embraces that stereotype in basically confirming that yes, Asian moms are badasses, brooking zero disobedience, caring not a whit for a child's preferences in activities or the precious Western value of "self-esteem."

I personally have no experience with Asian style parenting other than what I have read about or dealt with by seeing its results in adults. Yes, it's a common stereotype that Indian, Chinese, Japanese and Korean students will always - always - beat the pants off Western kids in anything academic. And Chua embraces that stereotype in basically confirming that yes, Asian moms are badasses, brooking zero disobedience, caring not a whit for a child's preferences in activities or the precious Western value of "self-esteem." In doing so, she hones in on what she perceives as the overwhelming weakness of the modern Western parent. We cave too much on TV and video games, don't emphasize academic achievement over all else, and are far too willing to allow children to "be their own people" at the expense of getting really good at the things that are required of them.

What upsets so many readers of her work is probably the fact that in a broad sense, she is right. I'm guilty myself of not being tough enough on many days, and in our moments of mutual exasperation over some kid fit of temper or disagreement, my wife and I have confessed to each other this concern.

Is it our American inclination towards democracy that makes us this way? Lord knows that living under the iron fist of various Asian dictatorships over a few thousand years has to trickle down to the home, and it's no surprise that our own bent toward self-determination has made its way into American parenting.

But even in applying the loose template of my own Southern upbringing - asking for a "yes" instead of a "yeah," when my own parents would have demanded it be followed by a "sir" or "ma'am" - I feel like I'm falling short some days. I wonder if I'm going to end up with brusque, backtalking children who answer with "WHAT!?" when they're called instead of the polite, respectful kids I know they can be.

But then I see other parents at the playground who are Silly Putty to their children's whims, who correct over-the-top misbehavior with a stammering Woody Allen-esque whine and a will like cold oatmeal, or simply ignore it as they gaze into the screens of their smartphones. Yet these same parents are shocked (pleasantly) when my kids display kindness to their playmates or respond to a question they didn't quite hear by saying, "Pardon me?" So deep down, I know my wife and I are doing something right.

In her writings, Chua brags about requiring her girls to play an instrument, as long as that instrument is piano or violin. She notes that whatever she asks her children to do (they are not required to choose any extracurricular activities), she demands that they be the best at it - no excuses. Failure (or even sub-par performance) is unacceptable.

With many American parents, it is true that mediocrity can become so acceptable that it ends up being the norm. Is there a reason to celebrate a B or a C on a report card? Shouldn't we always let kids know that we expect the best out of them? In her WSJ piece, she points out that many parents, seeing disappointing grades, will blame the teacher, the school or the curriculum rather than coming back to to the true culprit - the kid.

But Americans do know how to make demands on their kids. The only problem is much of that demand is limited to athletics. Our goal, if we want all American kids to compete on a global stage against the products of tiger mothers like Chua, is to reorient our focus and energy and add a uniquely American spin.

We should let our kids make limited choices (because where living in an Asian country has so often been about not having choices, that is what America is all about), but still demand excellence.

You want to play soccer? Fine, but no slacking, and as soon as your grades dip below a B, you're out. Asking for a drum set for Christmas? Great. You will take lessons and you will practice and you will rock out - no excuses. Slacking gets the set sold on Ebay. Entering the science fair? Fantastic. Shoot to win, not just participate - and no, a paper mache volcano is not an option.

It's probably not necessary to sit kids down for three-hour piano practice sessions with no water or bathroom breaks, as Chua describes doing. Nor is it necessary, as many American parents do, to constantly focus on the pursuit of Ivy League greatness at the expense of all else.

But it should be common practice that parents insist that in whatever they do, in wherever they seek from life, kids go out and kick ass.

And eventually, as Chua emphasizes, through persevering and eventually excelling, kids will realize their own strengths, achieve their own potential and be generally better adults.

-------------------------------------------------------

So, all this talk about hyper-achieving kids has me thinking about just one thing: Baljeet, the friend of Phineas and Ferb for whom no less than greatness is acceptable, and if he can't be graded on it (with an A, of course), he doesn't want to do it.

Ladies and gentlemen, the Baljeatles!